Inherently cringe

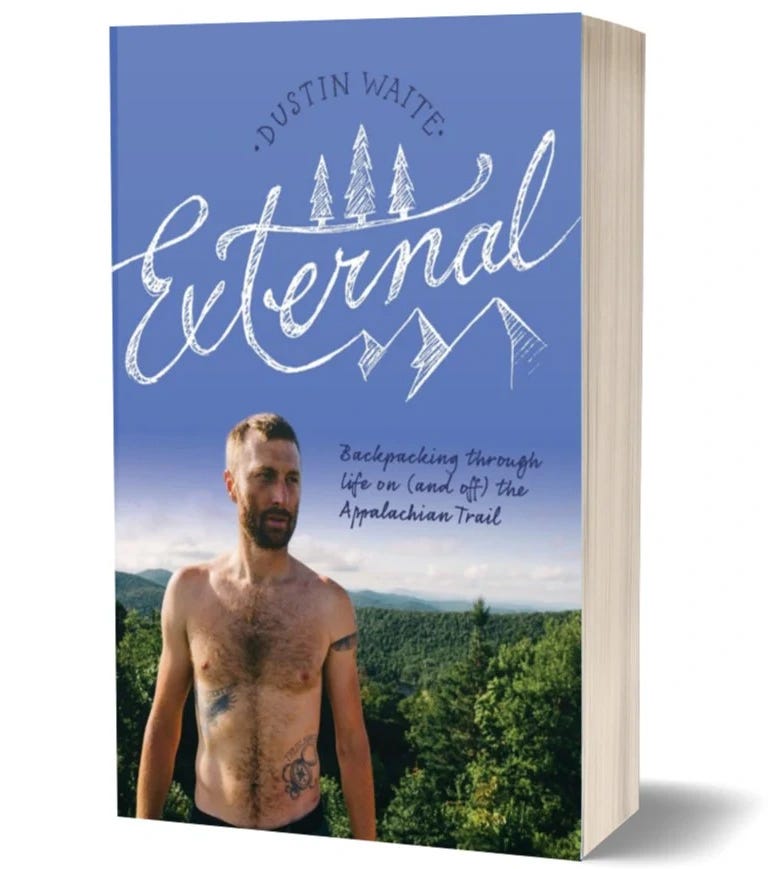

Review: External: Backpacking Through Life On (and Off) the Appalachian Trail

There’s something inherently a little bit cringe about trail journals. Nobody is immune—not Bill Bryson, not Cheryl Strayed, not Rusty Foster, and certainly not me. You’re stepping outside the flow of ‘normal’ human work and life for an extended period of time to push your physical and psychological limits and live in a tent and rarely shower and eat ramen on a regular basis and you’re also going to write about it and be introspective and put all that out on the internet (or into a book) for other people to read? Oh my god—how embarrassing. And how wonderful.

In many ways, Dustin Waite leans into this uncomfortable truth in his memoir External: Backpacking Through Life On (and Off) the Appalachian Trail. He lays bare some of the most vulnerable feelings one can have as a human, which others might gloss over or skip in a trail journal. But for Waite, it’s not just about the hike.

I met Dustin (trail name: Batman) in 2016, when I hiked the Long Trail. Waite was one of the many Appalachian Trail hikers on the Long Trail—the AT and LT overlap for about 100 miles—at the same time as me. We both stayed two nights at the Green Mountain House, a hiker hostel in Manchester Center, recovering as best we could from our overuse injuries. Waite had only recently gotten back on trail, picking up on an aborted 2014 thru-hike attempt, and so, like me, he didn’t quite have his trail legs yet.

He told me the reason he got off trail in 2014 had something to do with his heart, and with Lyme disease, but it was only after reading External that I learned the whole story.

Now, full disclosure, I actually read this book months ago (tore through it in two days) but the timing wasn’t right for a review. I’m going to do my best to remember the important bits without rereading all 320 pages now.

External is distinct from most trail journals in how much space Waite dedicates to writing about his life outside of hiking. Every other chapter bounces between time on and off trail. It is in many ways a kind of heroes journey, in which the Appalachian Trail plays a significant part, as Waite seeks—and, for the most part, seems to find—both social and self-acceptance. The prologue sets the tone for the rest of the book. It describes a youthful Waite’s deep feelings of social exclusion and depression, which lead him to an unsuccessful suicide attempt at the age of 13. These feelings continue to plague him, on and off, to varying degrees, throughout the memoir.

The hiking chapters are dominated by unfortunate accidents (losing the trail on his first night on the AT), backpacking feats (weathering a 30-hour snowstorm; hiking 41 miles in less than 14 hours), and other strange second-hand tales (like that of the trail angel who saw Walt Disney’s Davy Crockett being filmed as a child). Waite writes candidly about the unpleasantness, both physical and social, that can come with thru-hiking. For example, he arranges a ride into town on a freezing, wet day that a member of his own trail family (or tramily—groups of hikers that more or less hike together and stay at the same shelters or tent sites each night) steals before he arrives at the road crossing. Then, an unscrupulous shuttle driver charges more than they said they would, and the motel owner also quotes a different price in person than he had on the phone. After spending extra to secure a different hotel room for the group, the same tramily member who took his ride decides they want to stay in the hotel, too, so Waite ends up sleeping on the floor. Waite says he doesn’t hold any ill will, but I’m not sure I would be so forgiving!

The unfortunate incident to beat all unfortunate incidents began after Waite crossed the New Jersey-New York border: He felt his heart flutter strangely. And yet he kept walking, through New York and into Connecticut, and then into Massachusetts, still bothered by an irregular heartbeat and an odd shortness of breath for someone in otherwise peak physical condition. Eventually, he sought medical attention and learned that he had third-degree heart block. “The upper and lower chambers of my heart were not communicating and, like an engine with worn-out spark plugs, it had been misfiring for quite some time,” he writes. Blood tests found Lyme antibodies, and he was subsequently diagnosed with Lyme Carditis. The condition ended his hike that year, and he wasn’t able to return to the trail until August 2016. (Fortunately, he had been approved for health insurance mere weeks before this occurred. Thanks, Obama!)

Waite grapples with a lot of heavy topics in External, from mental illness and alcoholism to sexism, racism, and the overwhelming whiteness of the hiking community. In the hiking chapters, he expounds on the importance of Leave No Trace and picking up after yourself—and others—on the trail, and of not feeding wildlife. Drawing on his background in geology and environmental science, he includes brief digressions on natural history. In lighter moments, he delves into hiking debates around gear (he carries an external-frame backpack—hence the title—and lots of little luxury items), trail names (he chose his own), and the “purpose of the trail” (journey, or endurance challenge?).

The through line of the off-trail chapters is his quest to find meaning and purpose in life, and someone to share it with. He outlines a series of unsucesssful romantic relationships and the feelings of inadequacy and disappointment that follow. The most shocking of these is a brief, wondrous encounter with a bartender in Denver who stood him up on their second date. To Waite’s horror, when he eventually returned to the establishment where she worked and casually asked her coworkers about her whereabouts, he learned that she had been killed in a light rail accident (while out celebrating her birthday, I learned after Googling the incident). Waite is overwhelmed by an onslaught of emotion: sadness, at the woman’s death; guilt, for his unjustified anger at a non-existent slight; and a bit of relief, upon learning that she too had been looking forward to their next date. He vows to live life with more perspective: “There is nothing more detrimental to our happiness than when we choose to view something through a lens of negativity.”

Remarkably, the book ends on this optimistic note: He sets out on yet another first date. The Appalachian Trail may have been done and dusted, but the lifelong quest for happiness continues.

It can be uncomfortable reading someone’s desires and disappointments relayed so plainly, even if they are the same desires and disappointments all but the most sociopathic of humans experience. But that frankness is part of the appeal of External.

After finishing the Long Path in 2016, one of the essays I thought about writing was about all the sad men I met while hiking. Because so many of them did seem a little sad for one reason or another! But the catch was, I myself was a little sad at the time, which may have colored my impressions. (But then again, maybe not: The women I met all seemed optimistic and upbeat, or incredibly driven—either not sad, or hiding it better.) But of course, I don’t think that essay would have worked, because I really didn’t know jack about the people I met. You can learn a lot while hiking together for an hour or two, or staying at the same shelter, but it’s just a small sliver, really.

It was a rare privilege, and a pleasure, to read Batman’s story, the way he wanted to tell it.

Editor’s Note: Upon reviewing this draft, my editor pushed back on the idea that trail journals are inherently cringe. He does not find trail journals to be cringe, as a category, and suggested that I don’t really either. We discussed whether we might be using the word “cringe” differently, and that perhaps my definition is not so uniformly negative as his. He asked if I really think my trail journals, or my marathon essay, are “cringe,” and I said “yes, I do”! Like, a little bit, at least? Walden also came up.

My tentative working theory is that women overwhelmingly power the memoir-personal essay industrial complex (of which trail journals could be considered a subgenre) and that we’ve been told our writing is lesser (maybe even cringe!) and maybe this opinion is internalized misogyny? But I also don’t think cringe is an inherently negative characteristic, and that there’s something to embrace in this kind of introspection, which might, by some, be considered cringe. I would love others to weigh in on this debate in the comments!

Great essay. I can’t wait to read External! Not sure about the cringe analogy except that reading anything deeply personal makes me cringe a little but also relate to the person revealing feelings that we all (mostly) have.