My parents honeymooned in Big Sur after they were married. The ceremony was small—the only two people in attendance were my great aunt and uncle, R&R. My mom wore a light gray wool suit that I would have loved to have appropriated for myself, but when she took it out of storage when I was very small it was riddled with moth holes. (If that had happened more recently, I might have said don’t throw it out, I can fix it.)

After the wedding, R&R rented my parents a cabin in Big Sur. They spent their first day on a secluded beach nestled between the cliffs: lying in the sun, wading in the foamy water, and getting horrendous sunburns. I’ve heard this story over and over, so much so that it plays like a sepia-toned home movie in my head. There may be actual faded photographs somewhere that color this second-hand memory.

Growing up, California was one of the only places we vacationed—maybe the only place. My parents are glassblowers, so they frequently traveled around the country for art fairs, often with me in tow, but California was one of the few destinations we visited solely for pleasure and relaxation, and to see family. (The only other vacation spot that comes to mind is the Arizona desert, where we would camp for a week in between art fairs. But I suspect that was as much a cheap way for young artists to spend the intervening days between work events as it was a vacation.)

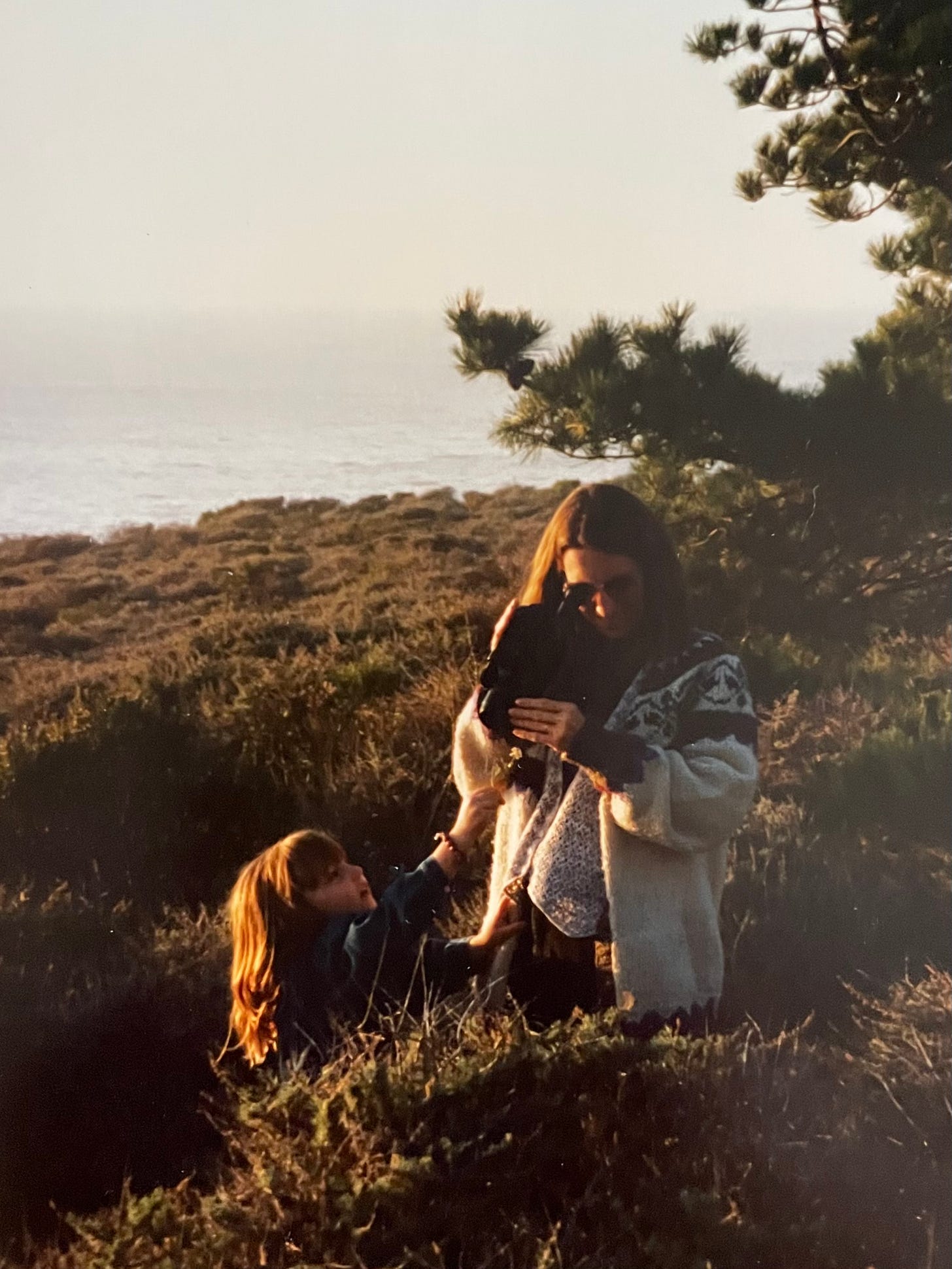

R&R, who are also my beloved godparents, had a beautiful house in Aptos. It was up on a hill with a view of the Pacific from the kitchen window and a swimming pool and hot tub in the back, overlooking a redwood forest. I took my first halting steps in that house as a baby (there’s most definitely home video of this). And on most of our visits, we would take a day trip out to Big Sur, and go out to eat at Nepenthe, which was the absolute height of sophistication in my young eyes. (Or it was until we went to San Francisco to see The Nutcracker one year—most of our visits were at Christmas—and ate at a restaurant that served sorbet as a palate cleanser between courses.) These day trips to Big Sur were part of a tradition that had been around longer than I have been alive, longer even than my parents had known each other. When my mother was in high school, she ran away from home, and stayed with R&R and her two small cousins for a season, and visited that same honeymoon beach with them. In some ways, R&R were like substitute parents at a time when she needed them, and California her home-away-from-home.

In short, my mother loves California, and especially Big Sur, and I absorbed her delight and enchantment as though through osmosis.

So it’s little wonder that when I first decided I wanted to run a marathon, I landed on Big Sur first. Unfortunately, that was sometime in late spring of 2022, and the Big Sur marathon had just taken place. I didn’t want to wait a year to run a marathon; I wanted to do one that fall. The Mount Desert Island marathon in Maine was the next best thing: beautiful, rugged, remote, and even smaller and more low-key.

After that race, I thought that if I were to ever run another marathon, Big Sur would be at the top of the list. I decided to enter the lottery every August until I got in. I struck out in 2023—which was maybe all for the best, because the 2024 race was an out-and-back instead of point-to-point. Shortly before the race was to take place, part of a cliff and large chunks of Highway 1 collapsed into the ocean after days of heavy rain. But in 2024, I got in, either because I entered as soon as the lottery opened, or because fewer people applied because it was unclear if the road would be repaired before the 2025 race.

I joked that I would run with an extra light step, to avoid triggering another road collapse.

On the morning of the race, I climbed onto a school bus in Monterey with dozens of other runners a little after 3:45 am. It was misting when we left—not quite raining, but wet like a heavy sea spray. One of the people waving us off said it was the last of the rain, but he was very much mistaken.

We drove to the start line in the dark. I drank the hot coffee my mom had woken up to prepare before she drove me to the bus pickup, and ate a cereal bar. The sweet scent of the banana my seatmate ate was intoxicating, and I wished I had thought to buy one the day before. I could see nothing of the rugged coast out the window, but could feel the steady climbs and descents on the road beneath us.

The sky was beginning to pale as we approached the start line, and it was still misting when we climbed off the bus. I pulled my fleece sweatshirt back on before locating my corral and the portapotties and the coffee, in that order. I shivered in the bathroom line and somehow struck up a conversation with another runner, who began telling me about a very cold race “back where I’m from,” which of course was New Hampshire (where I went to high school) and (I knew before she even said where she was from) the race was Millinocket, the free marathon in Maine that takes place in December. It’s run by the same people who put on the Mount Desert Island marathon, and the organizers ask runners to support the local economy in the former mill town in lieu of a race fee. (No surprise, I also sort of want to run Millinocket.)

After my first bathroom visit, I refilled my coffee cup and inserted myself into a huddle with the New Hampshire runner and her friend, who were both very friendly. It felt a little awkward, like a school orientation, but I was grateful to not be shivering alone. Someone had abandoned a banana at the coffee table, and after waiting a respectful amount of time to see if they’d come back for it, I accepted it as a gift from the gods.

As race time ticked nearer, I shed layers and pinned my bib to my shirt. I had just gotten to the front of the bathroom line for a second time when the first strains of “The Star-Spangled Banner” began playing, and everyone began moving towards the start line. Corral A was just starting by the time I joined the throngs. After a wry look at the sky, which was still misting heavily, I decided to wrap my sunglasses in my warm layers and put the whole bundle in my drop bag, which I could pick up at the finish. Not everyone took advantage of this. There were countless sweatshirts, bathrobes, and blankets draped over the security fences and in heaps on the ground. It’s assumed that at most races, these items are donated, but on the off-chance that they aren’t, I chose to send mine to the finish line. I had even asked my mom to bring clothes she wanted to get rid of, before I knew I would have a drop bag, so that I could abandon them guilt-free if necessary. But cleaning and drying those masses of wet clothes so they are in a condition to donate seems like a massive project, and I didn’t want to risk my items ending up in a landfill instead.

Corral B was off. My arm hair was standing on end and beads of water clung to the strands as we began shuffling towards the start line.

The race begins at Big Sur Station, an information and emergency services hub for Big Sur residents and visitors. It’s located along a stretch of the highway set back from the coast, lined with coast redwood. When we finally began running, and left the shouting emcee behind us, I was amazed at how quiet it became—just the sound of hundreds of footfalls, of slow inhalations and exhalations, and an effervescent sizzle of rain.

Redwoods are so tall that they almost stop seeming like trees, unless you tilt your head back to look up at them. For the first few miles the forest completely enveloped us, except for a few places where it opened up to reveal a small gas station, shop, or restaurant. A handful of locals braved the rain to cheer us on, swathed in ponchos or holding umbrellas.

After we emerged from the forest, the road cut across an expanse of hillside, sloping down to the sea. Some of these were dotted with cows, and the tell-tale yellow flowers of invasive black mustard. Black mustard flowers are lovely, but the plant produces allelopathic chemicals that prevent native plants from germinating.

Without the protective tree cover, the wind picked up. My shorts and t-shirt were plastered to my skin with rain, and I started to feel rather cold. All things considered, the conditions were better suited to a moody walk on the moors in a hunting jacket followed by a hot beverage and a sit by the fire than they were for running for hours on end in a t-shirt and short shorts. I hadn’t even worn a cap to keep the rain out of my eyes, because on my windy winter training runs, I realized it’s a huge pain to have to keep reaching up to keep my hat from flying off. Still, better to be cold and wet than hot. Later, E and my mom would tell me that the local news reporters covering the race couldn’t stop talking about how unusual it was for the weather to be both rainy and windy; usually it’s sunny and windy or foggy and calm.

Even though it was raining, it was clear enough to see out to the ocean, at first in the distance, shades of blue and lines of white, and then, as we reached the edge and began to climb, right there beneath us, a tempestuous soup. At some point a flock of pelicans flew by, large and majestic and distinctive enough to identify from afar.

There are several strategically placed musical groups along the course, and the first are the Taiko Drummers, about halfway up Hurricane Point—a two-mile, 500 foot climb. Their drums were covered in protective plastic to shield them from the rain. The wind picked up as we crested the hill, and I leaned into the long downhill to Bixby Bridge, where there was someone playing a grand piano beneath a flimsy plastic canopy.

We crossed the section of road under construction following the partial collapse in 2024, which is still only open to one-way traffic. If I had had my wits about me at this point, I might have marveled at human ingenuity, and naivety, for building a highway on the “ragged edge of the western world.” (That’s the Big Sur Marathon slogan: “Running on the Ragged Edge of the Western World.”) The section of Highway 1 through Big Sur has been repeatedly blanketed by landslides, or fallen in chunks to the stormy ocean below, which is steadily eroding the cliffs beneath it. Climate change is likely making things worse: storms are rainier and more destructive, sea levels are rising, and wildfires burn through the region more frequently, destabilizing the ecosystems that knit the mountains together and making it more likely the whole thing will just wash away with the next storm. The state will likely continue spending tens of millions of dollars to repair the road and maintain the important cultural and touristic through-way for the foreseeable future. But what about the unforeseeable future? Like “last-chance tourists” visiting vanishing glaciers, I am glad I was able to run this race while I still could.

And then there’s the second-order joy of being able to use a space designed for and primarily used by cars, on foot, which is always a pleasure.

My observational and emotional powers were fairly exhausted by mile 18, and sometime between then and mile 20 I put in my earbuds and pulled up my marathon playlist. By then the rain had let up, and the wind had just about blown me dry. I stopped for a strawberry at the strawberry aid station, sponsored by Driscoll’s—we might have even driven by the very field from which this large, firm, tart berry had recently been picked earlier that week. Although the tops were trimmed off for us, half eaten berries littered the street.

The last few miles were a blur of hills, expensive looking houses with manicured gardens, cypress trees, glimpses of ocean. I had been warned about the Carmel Highlands, told that they could feel harder than Hurricane Point because they come so late in the race, and it’s hill after hill after hill, and the road banks sharply, forcing an uneven gait. But it was the tiny last hill on mile 26 that very nearly broke me—just 90 feet above sea level, and very nearly 90 feet too many for me. But, in the end, it wasn’t, and I coasted down to the finishing shoot, and saw E at the front of the spectators waving me in. I couldn’t see my mom in the throngs but she was there when I crossed the finish line, calling my name.

And—not that it really matters—but even though I stopped a couple times to take photos; even though it was hillier than Mount Desert Island, and rainy and windy; even though I waited in line to go to the bathroom mid-race; even though I took many more walk breaks, I still ran faster than I did in my first marathon. Not by a lot! But just enough for it to matter, just a little.

I found it almost impossible to not write at length about my conflicted feelings about whether or not to try to beat my previous marathon time or not, and to exhaustively detail the physical experience of running Big Sur. But, recognizing that may not be everyone’s cup of tea, I siphoned those thoughts into an entirely separate essay, which you can read here, if you want to know more about my race preparation, strategy, pace, and nutrition. It’s very exciting, I promise! It’s a lot like this post, but with blisters and chafing instead of flowers and birds. Read more here.

Congratulations! Great memories of your mom and godparents. What a wonderful place to have in your heart and mind. Your description of the marathon start and dilemmas of what to bring and what to wear during the race ring true to me. I make my first trip to the Monterey area in mid June for a wedding. I look forward to making my own memories there.

I loved this post, especially hearing about experiences with R&R, who are also my Uncle and Aunt! And your impressive completion of a second marathon; my hat is off to you.